Scientists want more science, more accurately represented, in the media. Yet I find they so rarely want to come on the radio and talk about it*

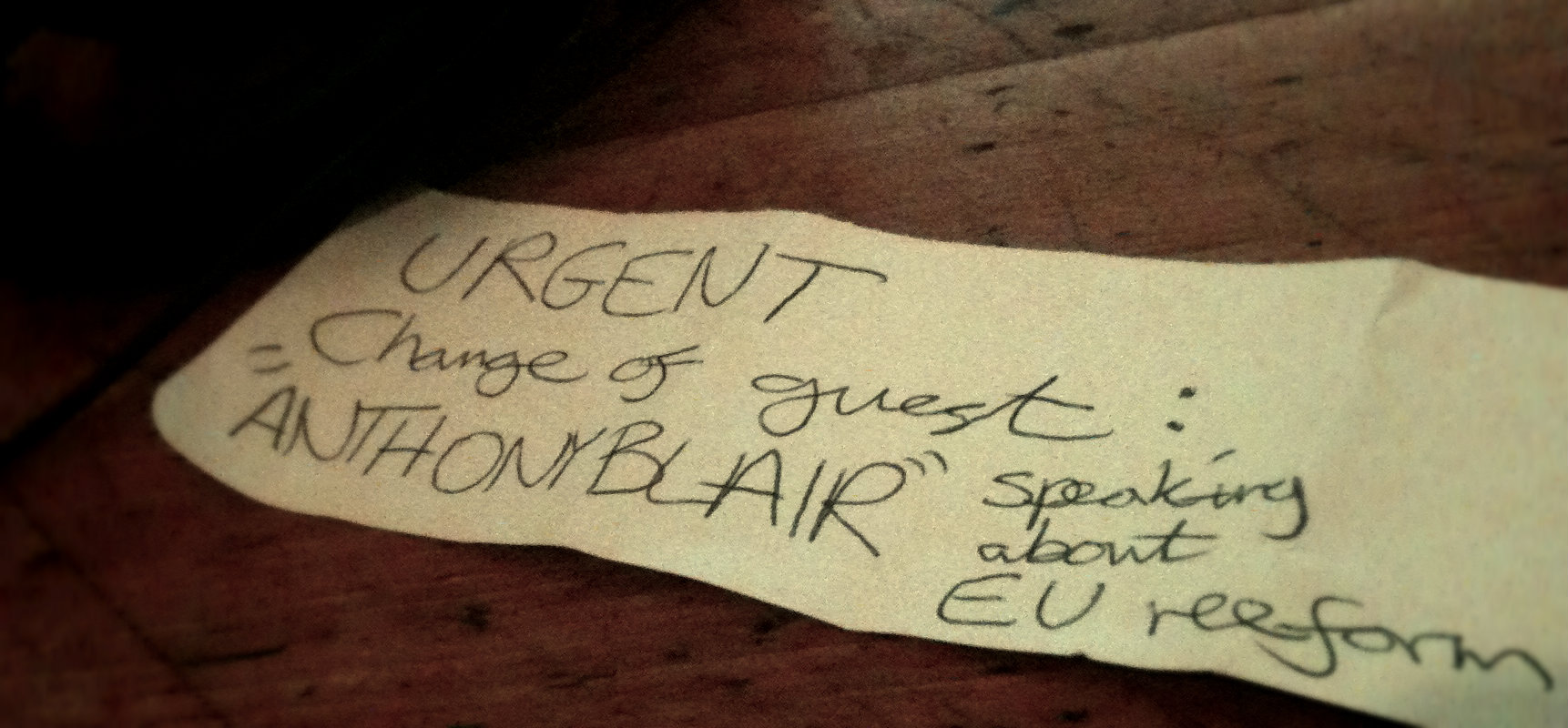

I work on a large daily current affairs radio programme, and certain big topics get covered frequently. The state of the economy, immigration laws, high-speed rail, welfare; those and many more get regular outings on air. Climate change is another topic that, in one form or another, will warrant regular discussion.

On most subjects, finding knowledgeable pundits on either side of the debate isn’t too tricky – especially for the ‘big topics’. But when it comes to climate change, something funny happens. In fact, it’s a problem more broadly across most scientific topics.

People don’t want to talk about it. Scientists – the ones who know their stuff the most – seem the most reticent to get on the radio to explain what they know.

Good scientists don’t want to go on air

From the many conversations I’ve had with scientists, university press officers and other science-representation groups, I believe the following to be true: the more specialised a scientist is, the less qualified they feel they are to talk to the media about it.

But why?

Science is a highly complex and specialised profession. Academics trade blows over incredibly niche little-by-little discoveries through peer-reviewed journal articles. The more you know about your specialist field, the more you think you’re not necessarily in a position to be ‘the authority on all of climate change’ (or whatever your specialism is) in a five-minute radio interview.

And, the more you know, the more you dislike the way your speciality is portrayed in the media. The less willing you are to devalue your work by debating it with someone who just hasn’t studied it like you have, and who is out of step with the scientific community.

But here’s the problem: that ‘someone’ is perfectly happy to be on the radio, and there’s a real danger your viewpoint – and more importantly your scientific research – won’t get properly represented.

Global warming sceptics are easy to book

Let me be more specific. Let’s take a basic “is climate change happening?” debate: yes or no. The following is absolutely typical in my experience:

I call round lots of universities and lots of climate change experts. They all say “yes it’s happening” but “no I couldn’t possibly come on the radio today…I’m not the right person for this”. Or, often, “no!! I won’t argue with a climate-change sceptic! They don’t deserve to be on. I don’t want to be party to giving their view equal weight in the debate!”.

Well, there’s one hour left until we’re on air, and at this rate your opponent’s viewpoint will be the only one that gets heard. What’s more – from the conversation I had with you – you sounded like the perfect guest. Please do the interview.

Meanwhile…I find that climate change sceptics are in comparatively short supply. Yet everyone I call on that side is willing to come on the radio in a heartbeat. So here we are in a situation where, because so many scientists are unwilling to come on the radio, the majority scientific viewpoint (in my experience) is in danger of being woefully underrepresented.

I must pause, briefly, to address a question some of you will be thinking:

Why must you represent the minority viewpoint at all? Surely that’s mis-representative?

I’m a radio producer and journalist. I’m not a scientist. I’m not an economist. I’m not a breastfeeding new mum. I’m not a ‘victim of the bedroom tax’. I’m not qualified enough on the vast majority of subjects we discuss to decide to completely silence a particular point of view. If people hold that opinion, it deserves some representation. So it’s my job to do that, rather than to unilaterally stifle particular sides of the argument.

And, as much as many in the scientific community dislike it – there are lots of global warming sceptics, not least our audience. And as with any media debate, if one side makes an overwhelmingly better case, that should shine through on air.

But if no-one’s willing to give that side of the argument, there’s a problem.

But I digress; for more on this particular debate I suggest you read this.

Scientists! Please embrace the media!

I know it’s easier said than done – but I really wish scientists were more happy to come on air. The fact is, the media ‘rules of engagement’ aren’t going to change. Sometimes you’ll only get a few minutes to discuss a HUGELY complicated topic. Sometimes you might have to debate with someone who you quite simply think is wrong and hugely underqualified. But those are the parameters in which the majority of the population will normally discuss your speciality, if at all.

And if you tell me you can’t come on the radio, or you don’t want to, I’m going to have to find someone else who can. And they may well know far less than you. And that’s not annoying for me because it makes my job more difficult. It’s annoying because I care deeply about doing my best to make sure scientific viewpoints are portrayed fairly and accurately to seven million listeners.

Thank goodness, then, for organisations such as the Science Media Centre. They get it – they fight to get science in the media, represented as accurately as possible. They’re adept at responding to media requests. For anyone grumbling about the under-representation or misrepresentation of science in the media – get behind these guys and help them do something about it.

Brian Cox is too busy to do all of the interviews on all of the science all of the time*. Scientists: science needs you!

—

*

Caveats!!

Coverage of science in the media is a gigantic topic – I could only mention one tiny point here. I’d like to give the above a couple of additional caveats:

1. There are LOTS of brilliant scientists willing to be in the media. I know that. My point is that there are, arguably, not enough!

2. There are LOTS of brilliant scientists willing to discuss climate change. And despite what I write above I’ve never failed to book the guests I need. However, by comparison with other professions, in my personal experience it can prove more difficult.

3. This is NOT a post about the way the media covers science – with the exception of the penultimate section. That’s a whole other debate.

4. Another ‘whole other debate’ is the way the media deals with the ‘climate change debate’ – where the majority of scientists would argue there’s no debate about whether climate change itself is happening. I appreciate that, but it is not my point – I merely use it as an example of an occasion where I’ve found many scientists hesitant to speak.

5. The headline of this article was an exaggeration, ok? (see points 1 – 2!).

6. I’m JOKING about Brian Cox!